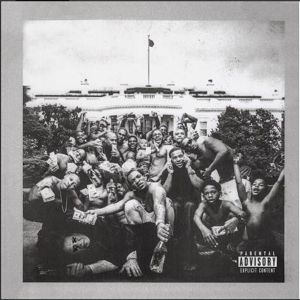

When Kendrick Lamar released his sophomore album, To Pimp A Butterfly (2015), I was in the middle of teaching a unit on Toni Morrison’s novel, The Bluest Eye (1970). My freshmen students were grappling with some big ideas and some really complex language. Framing the unit as an “Anti-Oppression” study, we took special efforts to define and explore the kinds of institutional and internalized racism that manifest in the lives of Morrison’s African-American characters, particularly the 11-year-old Pecola Breedlove and her mother, Pauline. We posed questions about oppression and the media – and after looking at the Dick & Jane primers that serve as precursors to each chapter, considered the influence of a “master narrative” that always privileges whiteness.

Set in the 1940s, the Breedlove family lives in poverty. Their only escape is the silver screen, a place where they idolize the glamorous stars of the film industry. Given the historical context of the novel, we can assume these actors are white. On the rare occasion that a person of color was cast in a feature film during this time period, they would surely occupy a subservient role – perhaps a butler or maid. So what happens when the collective voice of society perpetuates whiteness as the standard? What happens when children never see themselves as the superhero? the boss? the damsel in distress? the star? The master narrative tells us that white is good, pure, and clean. Perhaps most destructive of all though, it says white is beautiful.

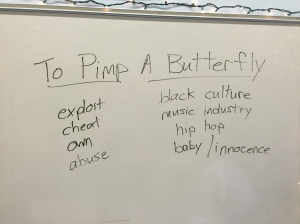

Butterflies are beautiful, too – and they are full of color. Butterflies are so beautiful, they can’t be made any more so. They can’t be manipulated, exploited, controlled, or confined. So why does America keep trying to do these same things to people of color? Why does America keep trying to pimp the butterfly? Surely we must know by now, the Civil Rights Movement was a metamorphoses from which we emerged into a colorblind, post-racial springtime, shedding the cocoon of Jim Crow, right?

It’s 2015 and Kendrick Lamar doesn’t think so. His album continues the conversation that Toni Morrison started in 1970. Inspired by the Black Is Beautiful cultural movement of the previous decade, Morrison offers a devastating critique of white supremacy. The Bluest Eye is arguably one of the most powerful novels about racism ever written. It critiques the media’s obsession with stars like Shirley Temple and Greta Garbo, revealing the psycho-social madness that results when a little girl becomes the victim of oppression directed inwards. She prays for blue eyes – her only wish – thinking it will make her beautiful. Why wouldn’t she? Morrison reminds us this message is everywhere, including “shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs,” and that, “all the world had agreed a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured” (Morrison 19).

Pecola Breedlove is the butterfly, still being pimped in 2015, and behind decades of mass incarceration, urban renewal, white flight, and gentrification, she’s now a middle-aged woman, hoping for change, hoping for springtime. Luckily, she has a soundtrack in TPAB.

While it’s problematic to cast Kendrick as a savior for hip hop and black America, it’s equally as dangerous to dismiss him. He offers a new brand of hope for the hip hop generation – one that is rooted in traditions of resistance and struggle. With pain and anger in his voice on “The Blacker the Berry,” Kendrick describes weeping, “when Trayvon Martin was in the street.” It’s easy to become devastated by the stagnation of race relations in America. But Kendrick is careful to balance the chaos with a clear and purposeful sense of direction – even when shining the light on his own hypocr itical double consciousness. So how do we help our students find hope amidst such chaos and contradiction?

itical double consciousness. So how do we help our students find hope amidst such chaos and contradiction?

My freshmen students were devastated when Pecola was raped and impregnated by her own father. Many school districts ban the novel for the graphic images depicting this scene. However, I’m willing to feel uncomfortable with my students if it means we can reimagine alternative realities for Pecola.

What would have happened if Pecola listened to Kendrick’s hit single, “i” which celebrates, “I love myself” in a world that tells black people not to? Would the outcome of the story, Pecola’s schizophrenic break with reality, have played out differently if she heard Rapsody’s stand-out verse on “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” where she raps about self-love. I’m not arguing that music could have prevented Pecola’s rape, or that we should assign blame to people who don’t know how to love themselves, but maybe Pecola’s blackness could have taken on new meaning and new beauty if she had influences like Kendrick or Rapsody. Perhaps she could have responded more critically to the cacophony of oppressive voices that enforce the master narrative and lead to internalized oppression for too many people. Morrison writes that the marigolds didn’t grow that spring. Nothing grew. The soil of that land was polluted, corrupted. It’s likely there were no butterflies that year.

When I asked my freshmen students if they saw any hope in the novel, their response was somewhat problematic. Most saw none. And I don’t blame them. The language is beautiful, but the narrative is bleak, dark, and depressing. But it’s what we do with our critical reading of the text that matters. It’s the honest conversations, reflections, and revised understandings that extend our reading onto the world around us. That’s where the promise of hope lives. One of my students, in a commentary response on my class blog, articulated this idea in a powerful way for all of us:

The novel represents hope because it is somebody taking notice and writing about all this oppression and racism. It brings attention to these serious problems and when people are aware, action follows. Even though Pecola’s story ends sadly, more hope is represented in Claudia [the narrator], for she does not totally succumb to the oppression. She pulls apart the [white baby] doll, questioning why it is so beautiful, [and] she has the strength to…pray for Pecola when Pecola is pregnant, planting the marigolds to help, and not judging like the rest of the town.

This is the kind of extended thinking that we want to illicit from our students. As Linda Christensen says, we want to teach for joy and justice, finding the hope in our critical readings and extending those understandings to the world around us. When I think about critical media literacy and Paulo Freire, I think about my students looking twice at an advertisement on their newsfeed – asking themselves questions like these:

- Who made this image?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is their agenda?

- Who does this image include? Who does it not include?

- Who has the power in this image? Who doesn’t?

- What beliefs, values, or ideologies does this image promote?

Our 21st century students are great consumers. They are saturated with information, media, and layers of subtext. If we don’t ask them to critique different kinds of media, to “read” the world through a critical lens, we aren’t teaching literacy at all. They must become producers of new knowledge and new understandings, new texts and new meanings.

If I pedagogically ignored Kendrick’s album release at a time when my students were reading Toni Morrison alongside articles about Mike Brown, Ferguson, #BlackLivesMatter – and considering the disposability of black bodies in an America that constructs a standard of beauty based solely on whiteness – I would have missed an opportunity to engage them in a pivotal conversation about race, hope, and justice. I would have missed an opportunity to speak to their hip-hop sensibilities – their hip-hop ways of being and knowing. I would have missed a chance to develop a set of profound connections to a popular culture text that is part of their lives. So here’s the first thing I did:

As students concluded their reading of the novel, I assigned a “Critical Lens Essay” that asks them to “look deeply at the text, think for yourself, and consider the kinds of oppression that are experienced by the characters in Morrison’s novel.” My initial essay prompt looked like this:

- What kinds of oppression do black people experience when the collective voice of society tells them they must adhere to white standards of beauty?

After listening to Pimp A Butterfly and noticing connections to the unit in every song, we studied some of the tracks, (which I’ll discuss later) and I created a second, optional prompt to choose from:

- How is the influence of the “Black Is Beautiful” cultural movement of the 1960s visible in both Toni Morrison’s novel, The Bluest Eye (1970) and Kendrick Lamar’s album To Pimp A Butterfly (2015)? Consider how both authors comment on how oppression manifests itself as internalized racism.

More than half my students opted for the second prompt, even though it requires more work. They must quote from both Morrison’s novel and Kendrick’s album as evidence – and discuss that evidence at length, demonstrating how it proves a carefully constructed thesis statement. I made a pedagogical decision to provide the “edited” or “clean” lyrics to a select group of songs on the album and I even posted a link to the “edited” version on iTunes. I know most students have access to the “explicit” version, and I would have no objections if they quote from these versions, but since these students are freshmen, some of whom might have parents that object to profanity, even when it’s being used for a noble, just, and artistic cause, I decided to give them access to a version without profanity. I find it problematic to call an album like this, “dirty.” Often times, with some of my older students, and in my after-school “Hip-Hop Lit” extracurricular class, I use the unedited versions of songs to maintain their artistic integrity – or to highlight their blatant violence, misogyny, or sexism.

The politics of hip hop education are complex. Students are assigned Vonnegut for summer reading, complete with multiple uses of the word “fuck” and a voyeuristic sexual scene that makes many adults uncomfortable, but we allow this, and in fact require it, because Vonnegut is white. He’s been accepted into the literary canon, and thus, his writing is considered “high art.” Hip hop is still the subject of intense, misdirected hatred and discrimination in schools. We aren’t protecting students from vulgarity when we forbid hip hop in the classroom. We are protecting ourselves from our fears about race – while simultaneously robbing our students of authentic opportunities to think critically about the media they consume. Literacy in the 21st century means bringing all different kinds of “text” into the classroom – especially hip hop.

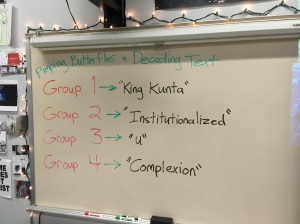

Before I assigned the second writing prompt, we did some close-listening to several songs on TPAB, specifically looking for Kendrick’s commentary on the kinds of oppression we learned about while reading The Bluest Eye. The levels of oppression that we focused on most were “internalized.” and “institutional” (there’s actually a TPAB track entitled “Institutionalized”).

The song with the most visible connections to Morrison’s novel is the track previously mentioned, titled, “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” where female MC Rapsody confesses that like Pecola, she was,”12 years of age, thinkin’ [her] shade too dark” and asks the listener, “when did you stop loving the color of your skin, color of your eyes?” In some ways, she’s speaking directly to the Pecola Breedloves of 2015, the butterflies who have been pimped into hating themselves.

Rhapsody goes on to declare, like Kendrick, “I love myself,” and encourages young black women to, “keep your head up,” because, “light don’t mean you smart, bein’ dark don’t make you stupid.”

Students pointed out that “Complexion” is about loving your skin tone, which reminded them of a video we watched in the beginning of the unit where young woman talked about bleaching her skin to appear more white. Students asked questions about the Zulus and became fascinated with the Zulu resistance to British colonialism, highlighting the counter-narrative that this song offers in response to institutional oppression.

When students listened to “King Kunta,” I showed them a clip from Roots, where 18th century slave, Kunta Kinte, who became a symbol for, “the struggle of all ethnic groups to preserve their cultural heritage,” refuses to adopt the white name of “Toby” – assigned by his white slave-master. I asked students, “why do you think he’s refusing to take the new name?” One student explained that, “Kunta” represents his identity – his African identity – it’s like what makes him who he is – and to give that up, is to give up his identity.”

After we listened to the track titled, “Institutionalized,” one of my students pointed out that her skin was like “an institution” keeping her trapped in a predetermined future, much like a correctional facility, hospital, or ghetto. She pointed to textual evidence in the song that suggests Kendrick is really talking about Compton, his hometown, as an institution, that keeps people trapped inside it, even after they’ve left. This led to a discussion about poverty as an institutional construct, rather than just a personal responsibility.

The last song we analyzed was “u.” Students noticed that Kendrick, or the speaker, seems to be talking to himself in the mirror, or at least to his inner demons, contemplating suicide. I asked them how Kendrick’s demons are similar and different to Pecola Breedlove’s demons. We considered the references to mental illness, stress, suicide, anxiety, and PTSD that surface throughout the album. These same kinds of deep, visceral responses to trauma can be seen in Morrison’s novel, as well.

My students are working on their essays now, pulling evidence from multiple sources, doing research, and looking at the relationship between two classic pieces of literature. One over 40 years old – and the other just 2 weeks young. Perhaps The Bluest Eye is like a parent to TPAB – Morrison ,a living moral ancestor to Kendrick. Educators can learn a lot from this album and its relationship to the young people in our classrooms.

[Note: To view some of the writing produced by students in this unit, read my follow-up post by clicking here]

[…] Lamar’s epic performance at the Grammys, you must grab this brilliant literary lesson I found here. The lesson uses Kendrick’s album, To Pimp A Butterfly, to help high schoolers develop a […]

[…] in its combination of grandness and precision — and, as such, his work deserves to be analyzed in college courses, not in quick blog posts. (I repent.) He’s also an artist bent on reminding his fans of his […]

[…] in its combination of grandness and precision — and, as such, his work deserves to be analyzed in college courses, not in quick blog posts. (I repent.) He’s also an artist bent on reminding his fans of his […]

of course white people think an uncle tom’s music is the pineacle of black music, want to teach something teach them about public enemy or krs one

[…] Article […]

Reblogged this on Cruising in Neverland.

[…] Mooney, Brian. “Why I Dropped Everything And Started Teaching Kendrick Lamar’S New Album.” Brian Mooney, 2015, https://bemoons.wordpress.com/2015/03/27/why-i-dropped-everything-and-started-teaching-kendrick-lama…. […]

[…] and even on subsequent encounters. Lamar’s 2015 masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly is already being taught in high school and college classrooms because it contains this kind of […]

[…] and even on subsequent encounters. Lamar’s 2015 masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly is already being taught in high school and college classrooms because it contains this kind of […]

[…] and even on subsequent encounters. Lamar’s 2015 masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly is already being taught in high school and college classrooms because it contains this kind of […]

[…] and even on subsequent encounters. Lamar’s 2015 masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly is already being taught in high school and college classrooms because it contains this kind of […]

[…] https://bemoons.wordpress.com/2015/03/27/why-i-dropped-everything-and-started-teaching-kendrick-lama… […]

[…] album received praise from music and social critics alike. Shortly after its release, it was even integrated into an English curriculum that taught Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. The blog post even made its way to Kendrick himself, […]

Reblogged this on Whatdoesbabysay?.

Thanks to my father who informed me about this blog, this blog is genuinely amazing.

I relish, cause I found exactly what I used to be having a look for.

You’ve ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

The article was instead catching and interesting enough to get all possible nuances to

remember. I do enjoy reading the material and the writing manner

of the author, etc as I did if finding https://billperlmutterphotography.com/five-paragraph-essay/. I suggest you

write such kinds of articles daily to give the

audience like me all the essential information. In my view, it’s better to be ready for all the unexpected scenarios in advance, so

thanks, it was pretty cool.

I’m an IB teacher, an old white guy, teaching in Shanghai. Any suggestions on how to approach Lamar’s songs with the respect they deserve as texts and works of art, without appearing to patronize or pander? I’m thinking of pairing it as an IB text with “Their Eyes Were Watching God”.

[…] by people like Brian Mooney, an educator who authored a viral blog post entitled: Why I Dropped Everything and Started Teaching Kendrick Lamar’s New Album , in which he argues that its time to start rethinking the literary canon, I began creating […]